Story: Prof. Dr. Trinh Sinh

Photos: Amachau

The Muong are one of Vietnam’s four most populous ethnic groups. French scholars were the first to conduct systematic studies of the Muong, including Pierre Grossin, who observed that the Muong lived in concentrated mountain communities and titled his 1926 monograph The Muong Province of Hoa Binh. This was one of the earliest works to formally identify the Muong as a distinct ethnic group. Soon after, ethnologist Jeanne Cuisinier spent 15 months in Muong regions, and after nearly two decades of research, produced a landmark study: The Muong – Human Geography and Sociology.

The Muong and the Viet (Kinh) share common origins, both descending from indigenous peoples of the Hoa Binh culture more than ten thousand years ago. They later diverged under the influence of history and geography. The Muong remained in limestone valleys and foothill plains, while the Viet moved downstream to the river deltas and coastal areas. According to legend, they share the same ancestor – Hung King – whom the Muong call King Dit Dang

After the Hai Ba Trung uprising failed (40–43 AD), Ma Yuan ordered the collection and destruction of bronze drums to obtain materials for casting bronze horses to take back to the North; many Dong Son drums were lost. Yet the Han dynasty’s policy of destruction did not reach the Muong highlands. The Muong continued to use bronze drums in their life-cycle rituals, viewing them as inseparable from the national soul, as historical records note: “If the drum is lost, the destiny of the Man people is also lost.” The bronze drum remained a symbol of wealth and power among the Quan Lang (local chiefs): “one drum could be exchanged for thousands of buffalo and cattle.”

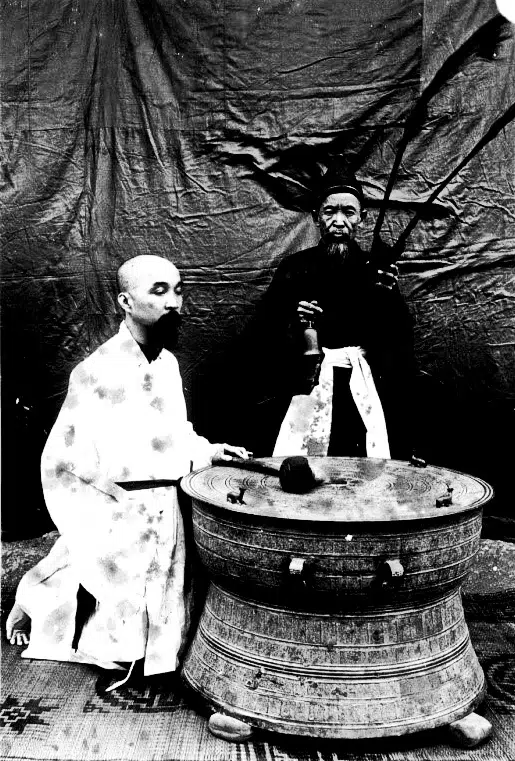

The sound of bronze drums continued to echo through distant forests and nearby villages. Their form and motifs evolved into the Heger type II drum – now known as the Muong drum – an enduring treasure linked to the Muong people from the era of Northern domination through the independent Ly, Tran, and Le dynasties.

The Muong drum’s form preserves elements of the Dong Son drum yet bears its own distinct beauty. The rim flares outward beyond the body, and the handles, unlike those on Dong Son drums, are set at the center of the body rather than at the junction with the back. The drumhead is often adorned with four to six figurative motifs, sometimes featuring stacked toads – symbols of fertility and abundance. The decoration consists of concentric or parallel geometric bands that completely cover the surface, evoking the colorful woven patterns that adorn the skirts and blouses of Muong women.

The French researcher Dr. Jeanne Cuisinier, a Sorbonne graduate and scholar of Asian beliefs and magical rites, formed a lasting connection with the Muong people in the 1930s, witnessing firsthand the bronze drum’s vital and enduring role in their rituals and faith. The Muong often buried bronze drums in tombs, bringing them out only when a Tho lang (regional leader or “land lord”) or one of his close relatives passed away. The drums were also played on festive occasions, including festivals, weddings, or to announce important news. When a Tho lang passed away, the family would summon a shaman (thay mo) to make the formal announcement. Standing at the entrance, he would call out three times: “My Land Lord has passed away.” Only then could mourning rituals – and the drumming begin. The bronze drum held a central place in the funeral rites of the Tho lang.

Muong legend tells how King Dit Dang, who ruled from the capital, once accompanied his younger sisters, Lady Ngan and Lady Nga, to wash their hair in a stream. As they combed their hair, they saw a bronze drum floating on the stream, drifting toward a sandbank. The king ordered his soldiers to retrieve the drum and summoned artisans from across the land to use charcoal as fuel and make molds to cast 1,960 bronze drums, gifting one to each land lord under his rule. This legend reflects the enduring bond between the Viet of the lowlands and the Muong of the highlands.

Archaeological evidence also confirms that in the Muong Dong Thech tomb complex in Kim Boi commune, Phu Tho province (a recognized National Relic), Muong bronze drums were buried as grave goods. The Chinese characters engraved on the slate “tombstones” surrounding the graves identify the site as belonging to local chief Dinh Cong Ky, who held the royal titles of Uy Loc Hau (Marquis) and Uy Quan Cong (Duke) – high-ranking positions in the Dai Viet court. He was born in 1582 and died in 1650, during the Le Trung Hung (Restored Le) period. The Le kings likely presented him with bronze drums bearing both Viet and Muong motifs, cast by lowland Viet artisans and brought to the highlands.

Muong people view bronze drums as their most sacred treasures. In the Lam Kinh region (Thanh Hoa), the Muong once welcomed visiting Le kings with a grand ancestral temple ceremony, offering four buffalo, sounding bronze drums, and greeting the royal procession with cheering soldiers.

Today, in some regions, the Muong still play bronze drums during festivals, and traditional Viet craft villages continue to cast drums for Muong communities. These enduring customs and beliefs preserve the cultural heritage of the Muong and serve as distinctive highlights for the development of local tourism.