Story: Nguyen Phuoc Bao Dan

Photos: Nguyen Phuoc Bao Dan, Ba Ngoc

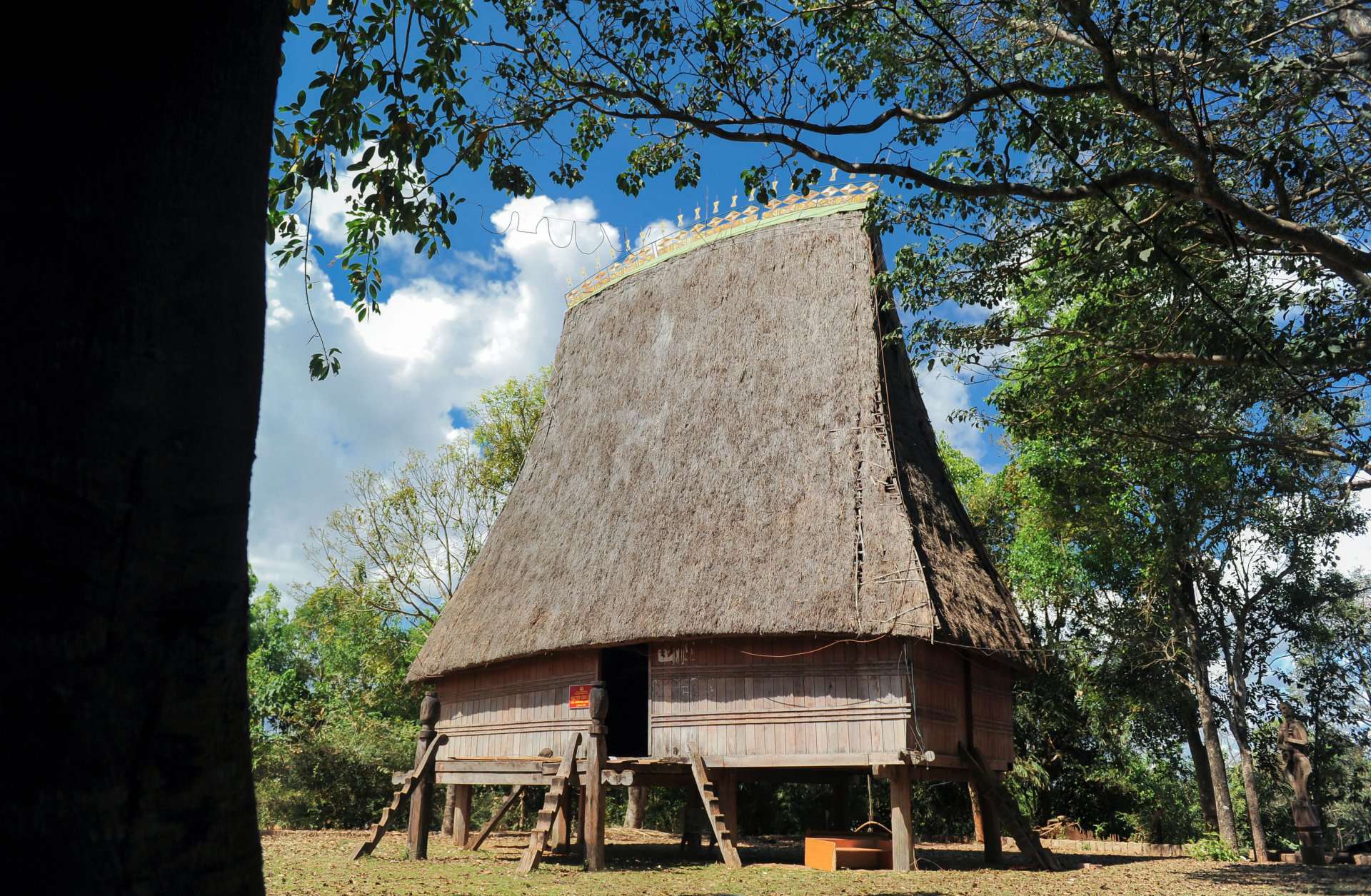

Traveling in the boundless green wilderness, lend your ears to the eternal tunes of epics beside a turf fire in a longhouse on stilts, cheered by glasses of liquor and melodious songs.

“Let’s strike the resounding ching cymbals – the cymbals of gold and silver echoes that roam far and wide, even when struck softly. Strike after strike, the house beams down below are shaken. The wooden rafters above tremble. Ring after ring, monkeys and apes do not bother to climb, goblins and demons forget to spook mortals, and squirrels and rodents can’t bring themselves to dig their holes. Snakes and cobras poke out and slither from all walks of life. Muntjacs stand in awe, rabbits sit in thrall, and deer can’t help but be stupefied…” (The Epic of Dam San).

The life of ethnic minority communities in Vietnam’s Central Highlands hinges on rotating crops, inhabiting well-defined areas, and complying with a hierarchical structure of hamlets governed by stringent norms and mores. The Central Highlands will enthrall visitors eager to gain insight into ethnic communities who traditionally practiced fire-fallow cultivation.

“Water flows from springs, people from a hamlet”. This profound saying accentuates an underlying meaning. In a region where people survive the seasonal dichotomy of the rainy and dry seasons, water is as valuable as gold. This applies to mortals, as their lives drift with the ebbs and tides of their communities, and co-existing, communal structure in all aspects of life.

Take the Ehde as an example. A newborn infant undergoes an ear blowing ceremony, a compulsory ritual. It is not until after this ritual that the infant can hear, see and resonate with his community. Many other rituals follow when the infant grows up, marries, begets children, and passes away in the closed circle of life. Other rituals related to slash-and-burn cultivation practices, such as field-burning, seeding, the new harvest ceremony, and housewarmings, etc., are closely linked to the community, and held for the sake of common prosperity. As a manifestation of cultural interdependence, performances of epics are of indispensable importance.

Epic storytellers

Khan of the Ehde, H’ri of the Jrai, Ot N’trong of the Mnong or H’amon of the Bahna, etc. Different communities have different names for their epic treasures. The Dam San, Khinh Du, Dam Di… Dăm Phu, Gi Dông, Jing Chơ Ngă, Xinh Nhã… These are epic portrayals of life, customs, the desire for liberty, love, affluence, and power in a hamlet. The native tribes of the Central Highlands were nomads, drawing their livelihoods from the forests.

Nowadays, life in various residential hamlets in the Central Highlands has changed and modernized. However, many majestic wharfs have been preserved. Sources of water, these wharfs are also performing spaces for epics during the wharf cults, a crucial rite in an average Central Highland community.

The same applies to the longhouse on stilts. The turf fire, a k’pan stool, and a jar of pipe liquor form some recognizable backdrops for the epic. The epic is characterized by rhythmic verses and dialogue, or flexible improvisation linked to the performing sphere, the context, or the storyteller.

A key characteristic of an epic is the repetition of various paragraphs. They are repeated for the audience to learn by heart. They are repeated and taught to the young. Many youngsters are fond of epics. They say the genre is difficult to learn and memorize because its language is old-fashioned and out of context in modern society. However, through repetition, they absorb the beauty and magic of the epics are able to sing and recount them. They are chosen to inherit and nurture the survival of these cultural seeds.

By the cozy hearth of a longhouse, beside a flaming fire and rows of Tuk and Tang liquor jars, the Gol lute plays, the Đĭng năm, Đĭng vuốq and Đĭng tak ta lutes murmur gracefully, accompanying the rhythmic songs of the storyteller, who is surrounded by keen youngsters sitting in deep contemplation.

Their minds are occupied by a vision of the hamlet in its heyday, looming out of the unfathomable green. Their hero Dam San succeeds in his struggle against cuê nuê (the thread lengthening custom) and in putting the hostile M’tao to rout. The indomitable Dam Di wins his naval battles. The strong hero Xinh Nhã beats his enemies, restoring peace to his hamlet. They live in nostalgia and fantasies that have long fed their spiritual vitality, against the urbanized backdrop of modern red basalt cities. Just listen to the wind across the mountains.