Story & Photos RESEARCHER VU KIM LOC

The chrysanthemum has long been known as the “Flower of Emperoi”, and is widely found on the jewelry and apparel of Vietnamese aristociacy.

Chrysanthemums are also present in a relief of Princess Mac Thi Ngoc Lam (16th century), preserved at Pho Minh pagoda in Nam Dinh province. The relief captures the viewer’s attention with 18 round marigolds with large petals and square florets that adorn the princess’s outer coat. In contrast, the flowers at her feet distinctively resemble golden everlasting chrysanthemums. The noble spirit of the princess is also represented by the knot on the front of her chest, which resembles two marigolds with its ruffled petals.

Chrysanthemums symbolize longevity and nobility in East Asian cultures. Japan’s Chrysanthemum Throne is world-renowned, while in Vietnam the flower long served as a status symbol for the old nobility. From the Dong Son culture of 2,000 years ago through the 20th century Nguyen Dynasty, the blooming chrysanthemum was a central motif on a wide range of imperial items from drums to thrones to steles to architecture.

One of Vietnam’s national treasures is a set of gold chrysanthemum plates owned by Princess Thuy Minh of the Ly Dynasty (1010- 1225). A treasure of the glorious feudal Dai Viet, the plates were intricately modeled with round florets and delicate petals. Their decorative patterns were quite distinctive, with three plates bearing floral motifs and the other two bearing phoenix and floral motifs.

Another notable example is a Chu Dau ceramic statue from the early days of Later Le Dynasty (15th century), currently exhibited at the Vietnam National Museum of History in Hanoi. Researchers have concluded that the statue depicts a noblewoman due to the motifs on her apparel and the presence of chrysanthemum jewelry, which represents purity and virtue.

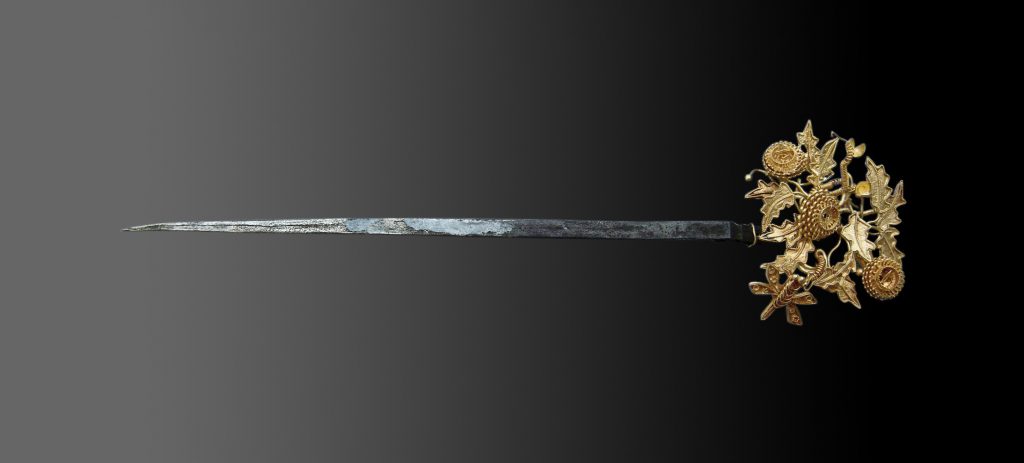

PRESENCE IN JEWELRY

The chrysanthemum was not only a status symbol and a herald of regality but was incorporated into noblewomen’s jewelry and everyday items as well.

A signature example is the chrysanthemum hairpin of one of Lord Nguyen Phuc Khoat’s (1738-1765) concubines, its silver body and elaborate top depicting a dragonfly landing on a chrysanthemum. The chrysanthemum is also present in brocade motifs uncovered in graves in Van Cat hamlet (17th century) and at the tomb of the mandarin Nguyen Ba Khanh, which can now be seen at the Museum of Ethonology and the Museum of Hung Yen Province.

The chrysanthemum was also featured on headdresses of the Nguyen Dynasty, from the “two dragons flanking the chrysanthemum” motif for mandarins to the “two phoenixes flanking the chrysanthemum” motif for Empresses and their ladies. The number of flowers denoted the station of the wearer.

Golden brooches of Nguyen-era noblewomen, meanwhile, represented the stations of their wearers with chrysanthemums featuring green gemstones fashioned into stamens.

While chrysanthemums are an enduring symbol of Vietnamese royal culture, they also remain a humble mainstay of everyday life. Historically associated with the power and privilege of the nobility, chrysanthemums are now offered to the Buddha and our ancestors with respect and reverence.