Story: Cao Trung Vinh

Photos: Phan Huy

Wooden-head puppetry (roi dau go, locally known as Oi Loi) is a distinctive folk art of the Red River Delta, traditionally performed as a key ritual during temple festivals at sites such as Keo Pagoda in Hung Yen and Co Le and Dai Bi Pagodas in Ninh Binh…

Many legends surround the origins of this art. One popular tale tells that during the reign of Emperor Thai To of the Ly dynasty, the empress remained childless. The emperor and his courtiers visited a pagoda to make offerings and pray. In time, the empress conceived and, after a full term, gave birth to a large bundle wrapped in membrane. When informed, the emperor commanded, “Take it away, lest ill befall me!” The midwife cast the bundle into the river, yet voices could still be heard within -crying, laughing, reproaching the royal father, and pleading for rescue.

While boating for leisure, Zen Master Tu Dao Hanh saw the bundle drifting by. He retrieved and opened it to find six infants with congenital birth defects. Moved by compassion, he brought the babies to the pagoda to raise and educate, transforming them into people of stature. The monk later created puppet plays to depict their story.

The puppets’ heads are carved from jackfruit wood to a uniform size, coated with natural lacquer, and vividly painted. Each head has a handgrip at the nape about 40 cm long (approx. 15.7 in), with an interior cavity about 30 cm across (approx. 11.8 in), and weighs around 3 kg (approx. 6.6 lb). Paired heads differ in facial color and contours. Kept behind the Buddha’s main altar, they are regarded as sacred effigies. After being honored with incense, the puppet heads are carefully stored and only brought out on traditional festival days.

Eagerly awaited by local residents, the Wooden-head Puppet Dance is a central rite of the Co Le Pagoda Festival, held each year from the 12th to the 16th day of the ninth lunar month. Before the dance, a ceremony is held to request permission to retrieve and escort the heads – reverently called the Sacred Effigies (Thanh Tuong) – from their sanctuary to the performance venue.

The accompanying music is entirely played on percussive instruments: two mo (wooden muyu) made from the base of bamboo culms; one trong ban (flat drum); two trong com (rice-paste drums); two thanh la (small gongs); one trong cai (grand drum) to mark time and cue melodic changes; one chuong dau (small ritual bell); and one trong thay boi (diviner’s drum) that follows the grand drum.

During the performance, each puppeteer manipulates two puppet heads. Their feet keep time with the rhythm, while their hands move the wooden heads in circular motions, extending them outward and then drawing them back to the chest in a gesture of offering.

The dance is structured around three basic movements set to a 1-2-3 rhythm, each repeated in three cycles. Every pair performs the nhay chau (homage dance) with the same steps and tempo, expressing the joy and relief of being saved and bathed in the pure river of the Buddha’s miraculous compassion. After five rounds of nhay chau, Ong Trang – the presiding guild leader – enters with slow, serene movements. His steps follow the drum’s pulse as they trace the shapes of Chinese characters: first chu Van, the Buddhist swastika, an auspicious symbol of Buddhism distinct from the Nazi emblem; then the phrase Thanh Cung Van Tue (“Long live the Sacred Palace”); and finally, Thien ha Thai binh (“Peace under Heaven”).

The music that accompanies the puppet dances is equally distinctive, with specific melodies for each segment: lan dieu giao (hymn), lan dieu dang (offering), lan dieu van (lament), lan dieu dua thu (dispatch), and dieu chinh phu (the conscript’s song). These pieces contain many archaic words; to interpret the texts, performers often turn to Nom dictionaries, though some terms remain elusive even there.

Wooden-head puppetry is a distinctive fusion of visual art, performance, and music. It endures as one of Vietnam’s surviving classical song-and-dance traditions and a cherished part of the nation’s cultural heritage.

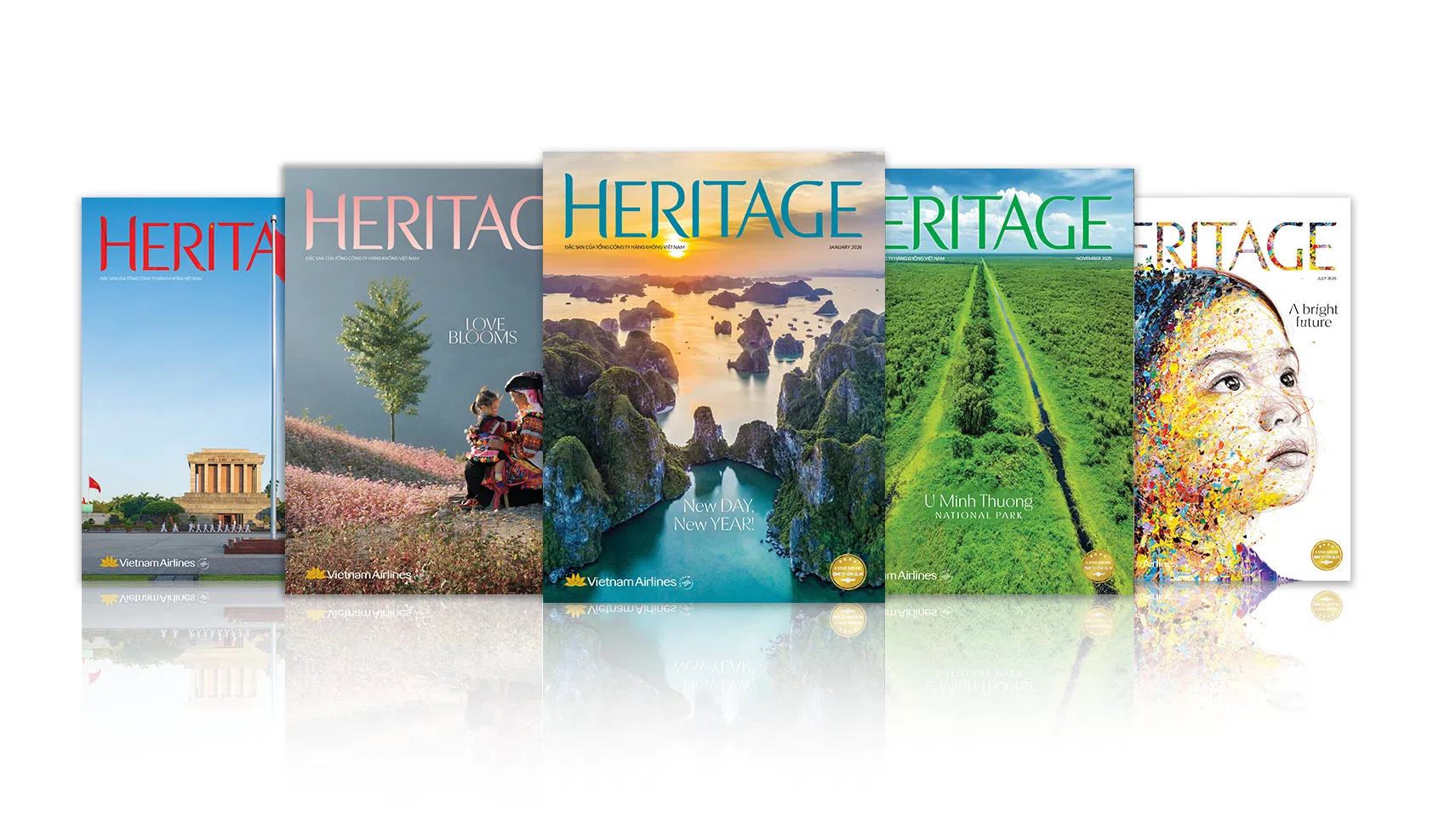

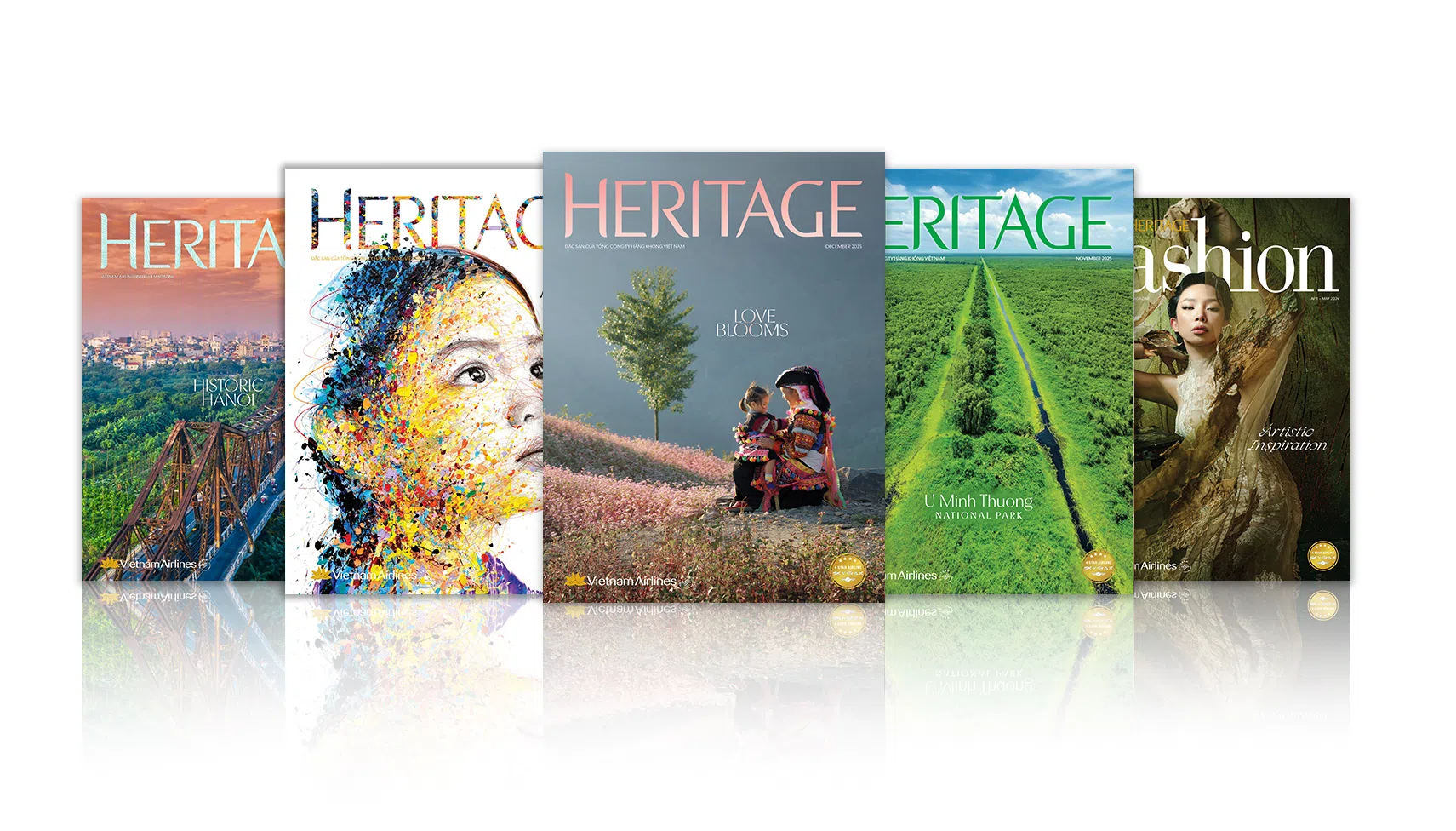

The photos illustrating this article received the Special Prize in the Cultural Heritage category of the Heritage Photography Award – 2024 Heritage Journey