Dr. Thuy Phuong

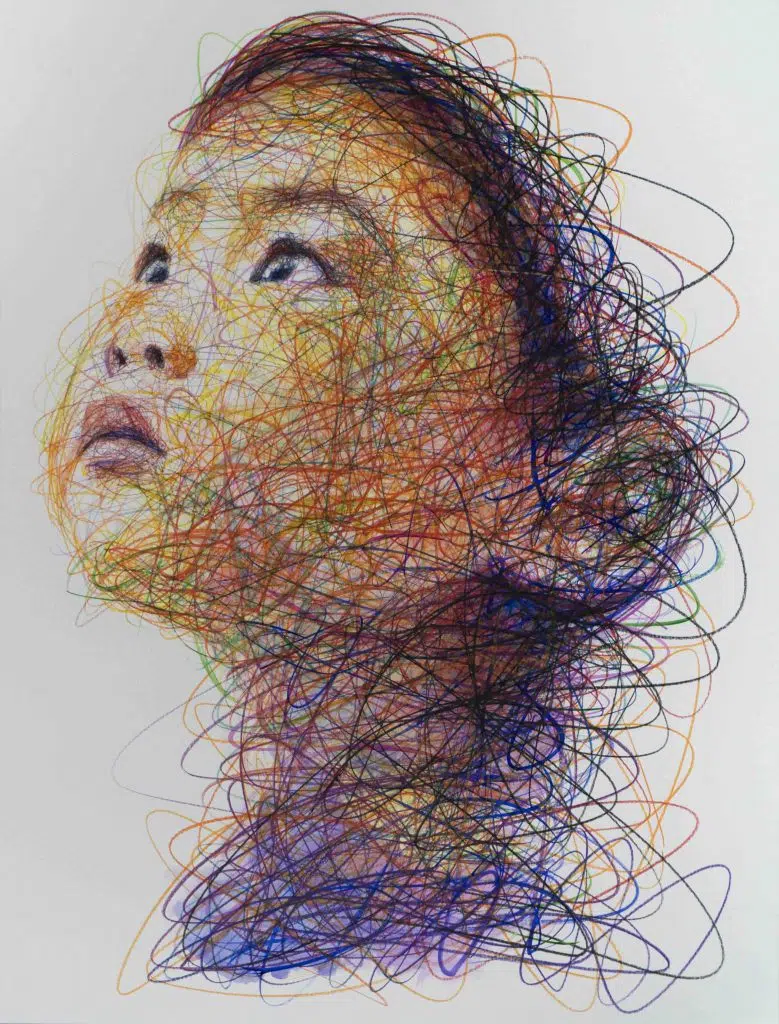

Hom Nguyen – a Paris-based painter of Vietnamese descent – is one of the most prominent names in contemporary art, once awarded the French National Order of Merit. A passion for painting, born from an unfortunate childhood, shaped him into an instinctive artist whose distinctive visual language leaves a lasting impression, one that focuses intensely on the emotional expressions of the human face. Though far from his homeland, Hom Nguyen has always remained deeply connected to his roots. Many Vietnamese faces have been reimagined by Hom Nguyen through expressive, impressionistic brushwork. Join Dr. Thuy Phuong and Heritage in a conversation with Hom Nguyen at his studio in Saint-Denis, Paris.

Let’s begin by revisiting your childhood. What kind of boy were you back then?

Sure, let’s go back! I was a boy who loved movement, always running around the neighbourhood with my friends all day.

Do you remember when you started drawing?

I must have been around six. I drew with a ballpoint pen on everything, scrap paper lying around the house, my skateboard, or anything that still had some space left to draw on (laughs).

And what did that little boy dream of?

That little boy lived with his mother, who was paralysed from the waist down, in a 13-square-metre apartment. We got by on a government allowance of around 400 euros a month. I never knew my father. My mother never spoke about him. I had to leave school early to help support her, so I never went to high school and don’t have a baccalauréat. Back then, my dream was simply to live a life of comfort and happiness. I always craved freedom and wanted to share that feeling with others.

Did little Hom ever feel lonely?

Of course. I was the only child of a single mother. But I wasn’t sad too often. My mother and I were very close and full of love for each other. She didn’t speak much but was always attentive to my needs. My mother had endured great misfortune; she had once even considered taking her own life. I knew she carried many secrets, things she never told me, but she completely trusted me. She was my guardian angel.

What do you think that childhood gave you?

It was a difficult childhood; it felt like a war. Sometimes sorrowful, sometimes full of optimism. Intense, but also filled with love.

Your mother was clearly a defining figure in your life. When she passed away, was that a turning point in your artistic journey?

Her passing was a huge shock. It was like an electric jolt that left me paralysed. I lost the most precious thing in my life, and suddenly, I had the overwhelming urge to draw, constantly. I started by painting on leather shoes, a craft I loved because it combined artistry and manual skill. But then something deeper stirred inside me, and I became obsessed with painting faces on canvas. That was also the time I decided to return to Vietnam for the first time.

So that moment of grief marked the beginning of your journey home, back to your childhood dream of painting, back to Vietnam, your mother’s homeland, your roots. You’ve painted so many faces. Why faces?

To me, a face is like a landscape. I see scenery in faces. It’s like being on a plane, looking down at the world. When you’re flying low, you can make out the houses, fields, roads. As the plane climbs higher, everything begins to blur and then disappears into the clouds.

was a sponsor of

the Solid’Art Paris

exhibition in 2024

When you describe it like that, I get the sense that viewing your paintings also requires movement?

Oh yes, absolutely! Come look at this piece with me. See, if you stand up close, you’ll notice just one face. Now step back a little, you’ll spot a second one – these are two children. Move back a bit further and you’ll see the face of the father emerging in the upper-left corner. You see? You have to move around to discover all three faces, a father and his two children. (He guides me to the painting as he explains.)

Wow, that’s fascinating! Looking closely at your work, I notice lots of vertical and horizontal strokes, so much movement in each piece.

To me, those strokes represent movement through life. At first glance, the eyes and their gaze catch your attention. But then, as you look deeper, you see vertical, diagonal, horizontal lines. That is the journey of life – mine, yours, all of ours – moving from darkness into light.

An art critic once said that your work has “connections to the Impressionist school” and reflects a “Zen-like philosophy”. Watching you paint in your studio, I felt like I was watching someone practise calligraphy. (laughs)

Calligraphy? Yes, maybe that’s true! Each painting is like handwriting, a visual script. It really is a form of calligraphy.

(2024), 120x120cm,

exhibited in Tokyo

You’ve had hundreds of exhibitions across continents. Which one do you remember the most?

Probably the one in Ho Chi Minh City. Not because it was my first show in Vietnam, but because it was held in the smallest room I’ve ever exhibited in. The simple, unpretentious space created an atmosphere of warmth and intimacy. The audience was sparse, but some elderly visitors stayed and talked with me at length. All of that touched me deeply and left a lasting impression.

Does Vietnam feel close or distant to you?

I am Vietnamese! Vietnam is always within me, it’s part of my present. My homeland is the red thread that runs through everything I do and everything I am.

Is there anything you still want to explore about Vietnam?

I’d love to deepen my understanding of Vietnamese culture. I feel that both Vietnamese people and culture are understated. Vietnamese art is raw, direct, never showy, and I truly appreciate that. It’s the direction I follow in my own work.

Have you ever feared losing your ability to paint, or losing your inspiration?

No, never! Painting is my breath, my life. If I painted just to earn money, maybe I’d worry. But that’s not the case for me.

How do you imagine yourself ten years from now?

I hope to be healthy and at peace, still able to share with the public through my paintings. You know, sometimes I’m deeply touched when I receive a message from a stranger – like once, someone from Hai Phong told me how much they loved my work. They even sent a photo of themselves standing in a banana garden (laughs). That kind of quiet joy, from home, that’s happiness.

Thank you for such a delightful conversation. Wishing you continued health!