Story NIKITA CHU

Photos LUXUO

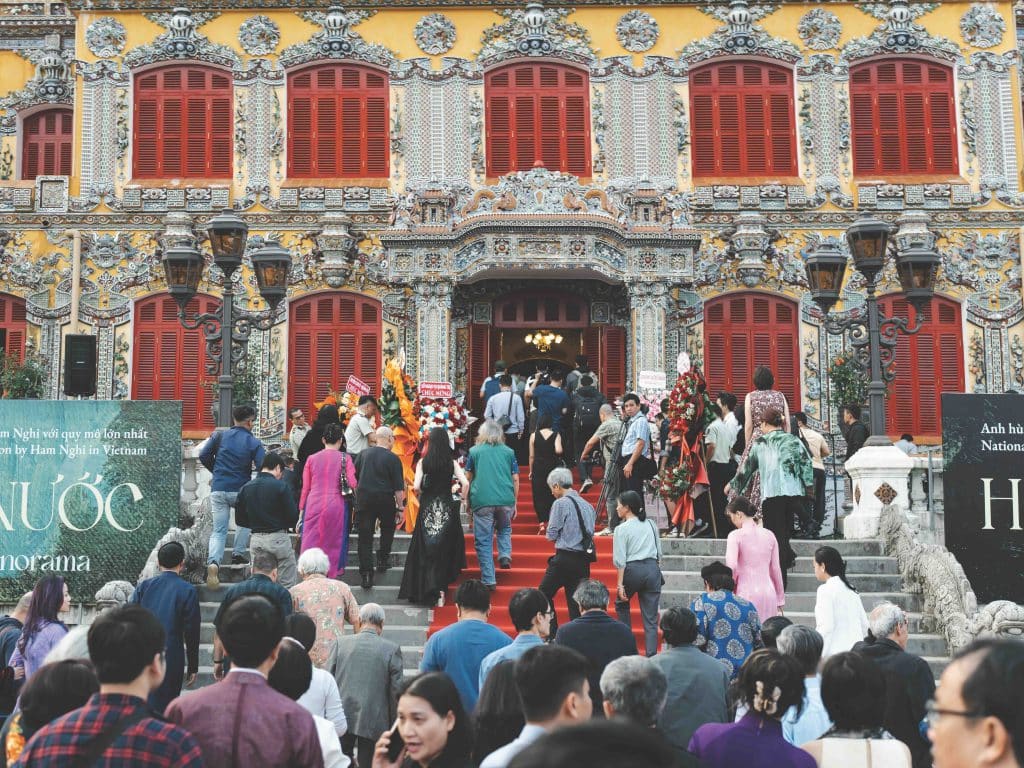

At the exhibition Troi, Non, Nuoc – Allusive Panorama, I had the opportunity to converse with curator Ace Le about the largest retrospective ever dedicated to the paintings of former Emperor Ham Nghi in Vietnam. Twenty-one works from ten private collections were displayed at Kien Trung Palace (Hue), offering art lovers and the public a chance to better understand his role as an artist, as well as the deep sentiments he held for his homeland.

It must be said that Troi, Non, Nuoc – Allusive Panorama is an exhibition that has entered the history of Vietnamese art. The event has passed, but it leaves a profound resonance in the hearts of the public. When comparing the initial aspirations of the project with the actual results, how do you feel?

Previously, few knew that former Emperor Ham Nghi was the first painter of modern Vietnamese fine arts. The goal of Troi, Non, Nuoc (Sky, Mountain, Water) is to restore former Emperor Ham Nghi to his rightful place in art history. This is something that Dr. Amandine Dabat – my co-curator – has tirelessly worked to realize for many years, especially through the publication Ham Nghi: Exiled Emperor, Artist in Algiers.

For me, this work was not simply about curating a retrospective exhibition. From the very beginning, I set specific criteria: it had to be held at The Imperial City of Hue, in the spring, with paintings depicting the life of the former Emperor as an artist, and all stages of implementation had to be carried out by Vietnamese people, according to international museum exhibition standards.

After a year and a half of preparation, with the support of many individuals and organizations, the exhibition was received beyond expectations, with 8,000 – 10,000 visitors per day throughout the two weeks it was open. Art lovers flew in from many countries and all regions of the country to Hue. Being warmly welcomed by the general public, art enthusiasts, and the people of Hue is the greatest gift for a curator – a bridge between art and the audience.

I still remember, before leaving the space, Dr. Amandine asked for 15 minutes to walk around the gallery one more time, lingering to deeply contemplate each painting; that was perhaps one of the most touching moments for me personally. Could you share about the common ground between the two curators, as well as the milestones that led to such a large-scale exhibition?

The first stage of the exhibition was probably when Ms. Amandine announced her doctoral thesis. The book based on her dissertation opened the door for the French public to discover the story of an exiled Emperor. The Vietnamese public only knew the former Emperor as a patriotic king, but not much about the artist Tu Xuan – Ham Nghi’s pseudonym, meaning “son of spring”. Throughout his life, he used this name as his artistic signature on his paintings.

As soon as I read Dr. Amandine’s thesis, I immediately felt that a retrospective exhibition of Ham Nghi’s works was essential for Vietnamese fine arts. The paintings needed to be gathered at least once, in the Imperial City of Hue, which he once called “home”, so that the public could see and understand him. The story of the former Emperor needed to be told in Vietnam, for Vietnamese people, with the sensibility and language of Vietnamese people. That is why I chose Troi, Non, Nuoc as the exhibition title, inspired by the poetry of Ba Huyen Thanh Quan, reflecting both the landscape themes of Ham Nghi’s plein air paintings and the hidden sentiments of an exile. Dr. Amandine immediately agreed with this title, as well as with my approach to structuring the curatorial narrative.

Could you elaborate further on that curatorial narrative?

The exhibition was divided into three sections. The first introduced the biography and places where former Emperor Ham Nghi lived. The second summarized the Can Vuong movement and its nationwide influence, with thirteen literary excerpts from twelve scholars representing the movement, presented through the calligraphy of Chau Hai Duong. The final section, also the heart of the exhibition, focused on Ham Nghi’s paintings.

In this section, Ham Nghi’s art was divided into three landscape genres: “Troi” (Sky), “Non” (Mountain), and “Nuoc” (Water), representing facets of his plein air painting style influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The “Troi” series reflects the panoramic perspective of a sovereign, with deep studies of changing light across the sky, along the horizon, and on the ground. The “Non” series contains two recurring motifs in Ham Nghi’s paintings: the image of a deserted road – symbolizing the obsession with the freedom of choice for someone placed on the throne at age thirteen – and the solitary ancient tree, evoking the position of a nation’s leader. Finally, the “Nuoc” series is arranged from dawn to dusk, or the different stages of a human life, revealing the former Emperor’s concerns and his ability to find beauty in every moment along that journey.

The audience also noticed how the curator subtly chose three colors corresponding to the three landscape themes: blue for the sky, earthy yellow for the mountains, and jade green for the algae beneath the water.

Thank you for noticing. Yes, every small decision in the exhibition design was the result of careful consideration and calculation. Another example: architect Chu Kim, project manager and exhibition designer, made a thoughtful suggestion – instead of hanging the paintings at a fixed height (as is common in most exhibitions), they were hung at alternating heights, reflecting the ups and downs in Ham Nghi’s life.

This was truly the most standout professional exhibition ever held in Hue. Surely there were many challenges during implementation?

Absolutely. Kien Trung Palace itself was not built as an exhibition space, so we had to plan carefully to ensure the safety of the paintings, operational feasibility, and project budget. Many stages required investment: specialized staff for packing and installing the paintings, refrigerated trucks for transportation, air conditioning systems for preservation during display, and CCTV to monitor the exhibition space 24/7. This was also the exhibition with a record number of visitors in my career, so crowd control and traffic management had to be meticulously planned. Without the flexible cooperation of the Hue Monuments Conservation Center and all production partners, the project certainly would not have succeeded.

And one of the greatest challenges was borrowing paintings for the exhibition. Ham Nghi left behind only about 100 paintings, so finding and persuading collectors to lend their works was a difficult process. The collectors all understood the importance of the project and invested resources to restore and preserve the paintings in time for the exhibition. To meet the strictest display standards, we searched for each antique French frame from the same era to visually unify the paintings.

After more than a hundred years, the paintings containing Ham Nghi’s personal sentiments have finally been brought together in a retrospective, something he probably longed for all his life. And surely, the former Emperor would smile knowing that his art is now being cherished in his homeland. On behalf of the audience, Heritage Magazine would like to extend our thanks and congratulations to curator Ace Le, Dr. Amandine, and the entire project team!