Story: Pham Minh Quan

Photos: Le Bich, Le Huy

Across history, myth, and art, the horse is a powerful symbol in Vietnamese culture.

Within the symbolic system of Vietnamese culture, each sacred animal carries its own layers of history and spiritual meaning. If the dragon and the phoenix are associated with authority and noble virtue, the horse represents dynamism, movement, and the act of opening new paths – qualities that have accompanied Vietnam’s agrarian and martial civilization throughout its long history. As the Year of the Horse approaches, this symbol feels closer than ever, inviting us to look back on the journey of a creature that has walked alongside the Vietnamese people, from myth and history to the arts of today.

From the earliest days of nation-building, the horse has appeared in Vietnamese legends. The iron horse of Saint Giong, breathing fire as it charged into battle, stands as a symbol of indomitable strength and the enduring wish for independence and self-determination. Throughout recorded history, the sound of hoofbeats has rung across every era of national defense and settlement. The warhorses of Tran Hung Dao thundered beside the Bach Dang River; the steed of Emperor Quang Trung carried him at lightning speed over the Truong Son range to Thang Long. In courtly life, the horse represented power, honor, and noble authority.

In spiritual life, the horse is believed to accompany deities on their journeys. Folk belief holds that saints and Buddhas travel by horseback when they descend to aid the people, quell chaos, or bestow blessings. For this reason, white or red horses are often placed at the feet of divine figures in places of worship, acting as sacred mounts that connect the celestial and earthly realms.

Among them, the white horse holds a special place. The legend of Bach Ma recounts how a white steed showed King Ly Thai To the vital earth-energy lines of Thang Long and guided the construction of the city’s citadel. When the horse disappeared at the shrine of Long Do, the king honored it as Bach Ma Dai Vuong (The Great White Horse Lord), later worshipped as one of the four guardian spirits of ancient Thang Long.

Beyond myth, the horse is woven into rural life and the popular imagination. Vietnamese proverbs and folk verses capture its character: Ngua anh di truoc, vong nang theo sau (“The man rides ahead on his horse, the woman follows in her palanquin”); Thang nhu ruot ngua (“Straight as a horse’s gut”); and Ngua hay khong quan duong xa (“A good horse cares not how long the road is”). Together, these sayings cast the horse as strong, loyal, and unyielding – an enduring emblem of perseverance.

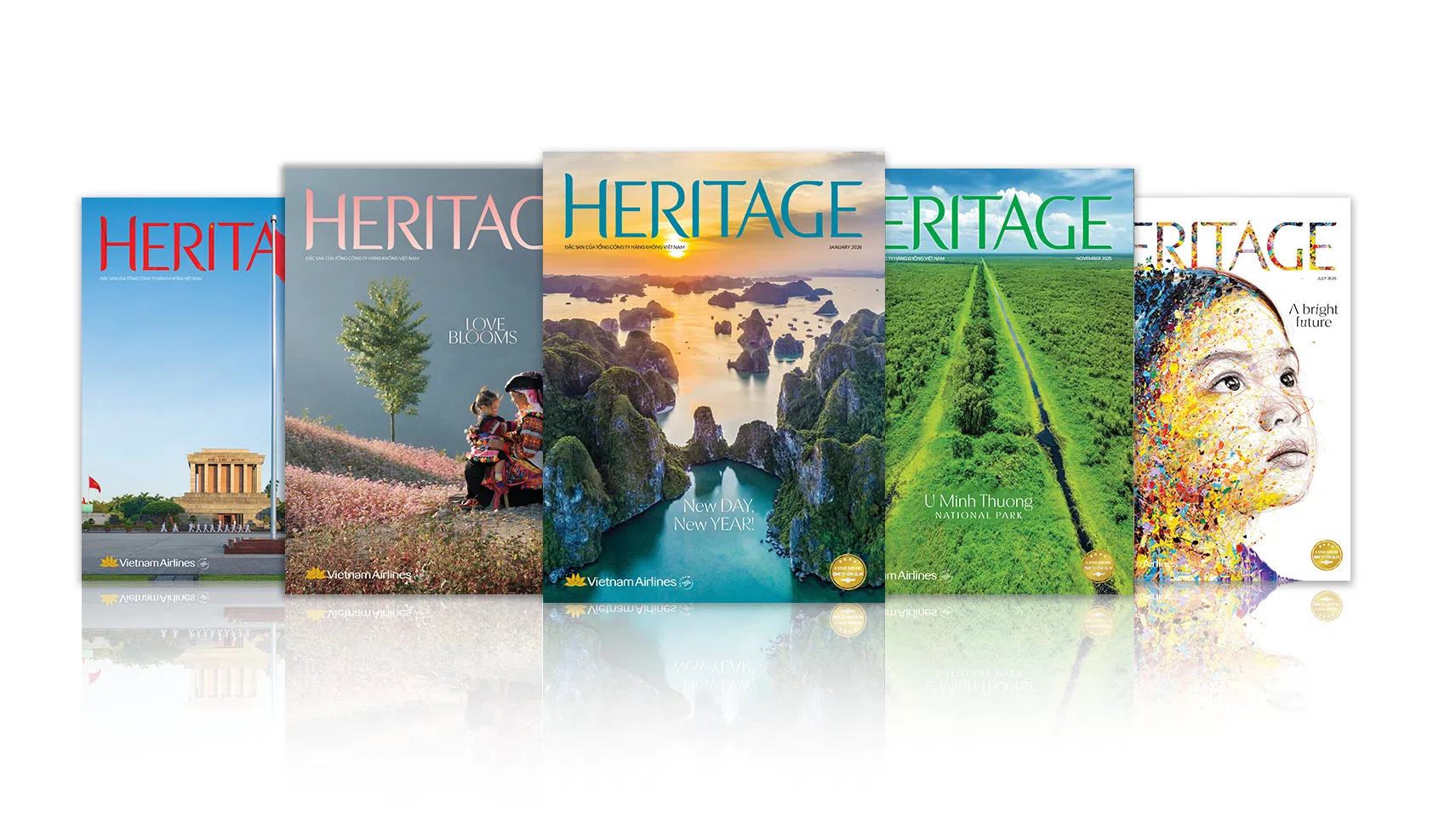

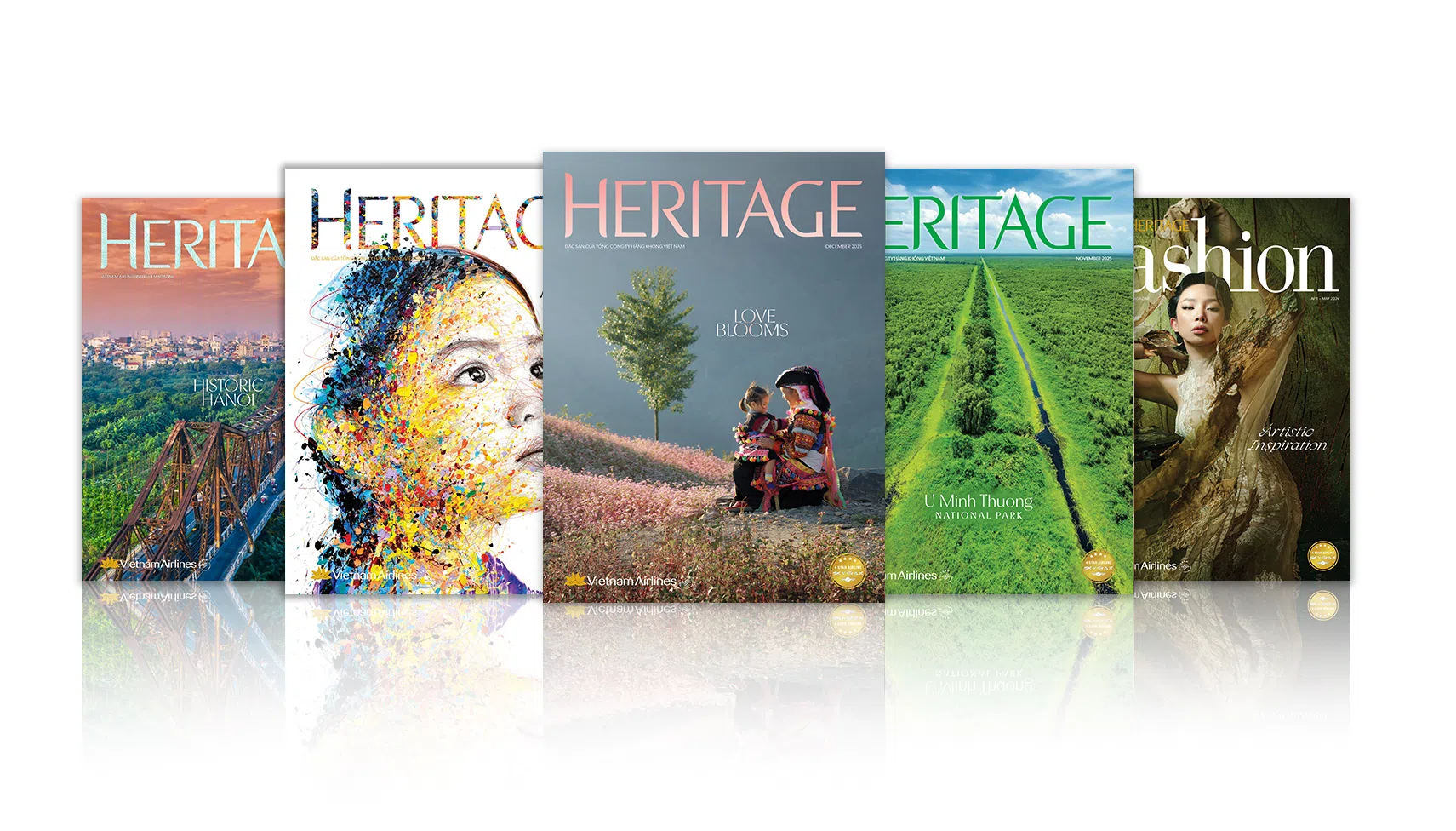

In folk painting genres – from Dong Ho and Hang Trong to Kim Hoang – the horse appears in many familiar narratives: Phu Dong Thien Vuong routing invaders, a successful scholar riding home in glory, or Emperor Quang Trung leading his troops into battle.

To welcome the Year of the Horse, pairs of prints depicting horses are hung beside doorways or on either side of the ancestral altar to create a sense of warmth. People also hang paper horses from peach branches to invite good fortune. The restrained palette of plant dyes, charcoal, and red pigment gives these folk prints a gentle, earthy charm, placing the horse firmly within everyday life as a symbol of nature and resilience.

In traditional Vietnamese sculpture, the horse appears in varied and vivid forms, reflecting both authority and folk life. At the royal tombs of Gia Long, Minh Mang, and Khai Dinh in Hue, pairs of stone horses stand solemnly like royal attendants, their powerful bodies and finely carved saddles and bridles evoking the dignity of the Nguyen court. By contrast, the horses at Diem communal house in Bac Ninh are charged with drama: arched, muscular bodies and riders in everyday poses create a strong sense of movement and narrative. At Ha Hiep communal house in Hanoi, horses appear in scenes of processions, hunting, and racing, lively fragments of village festivals carved into wood. Meanwhile, at Dai Phung communal house in Hanoi, a warhorse surges forward with a dragon’s head rising behind it, blending physical force and sacred energy – a symbol of heroic power that protects the people, and of a beauty that reconciles the real and the sacred in the Vietnamese imagination.

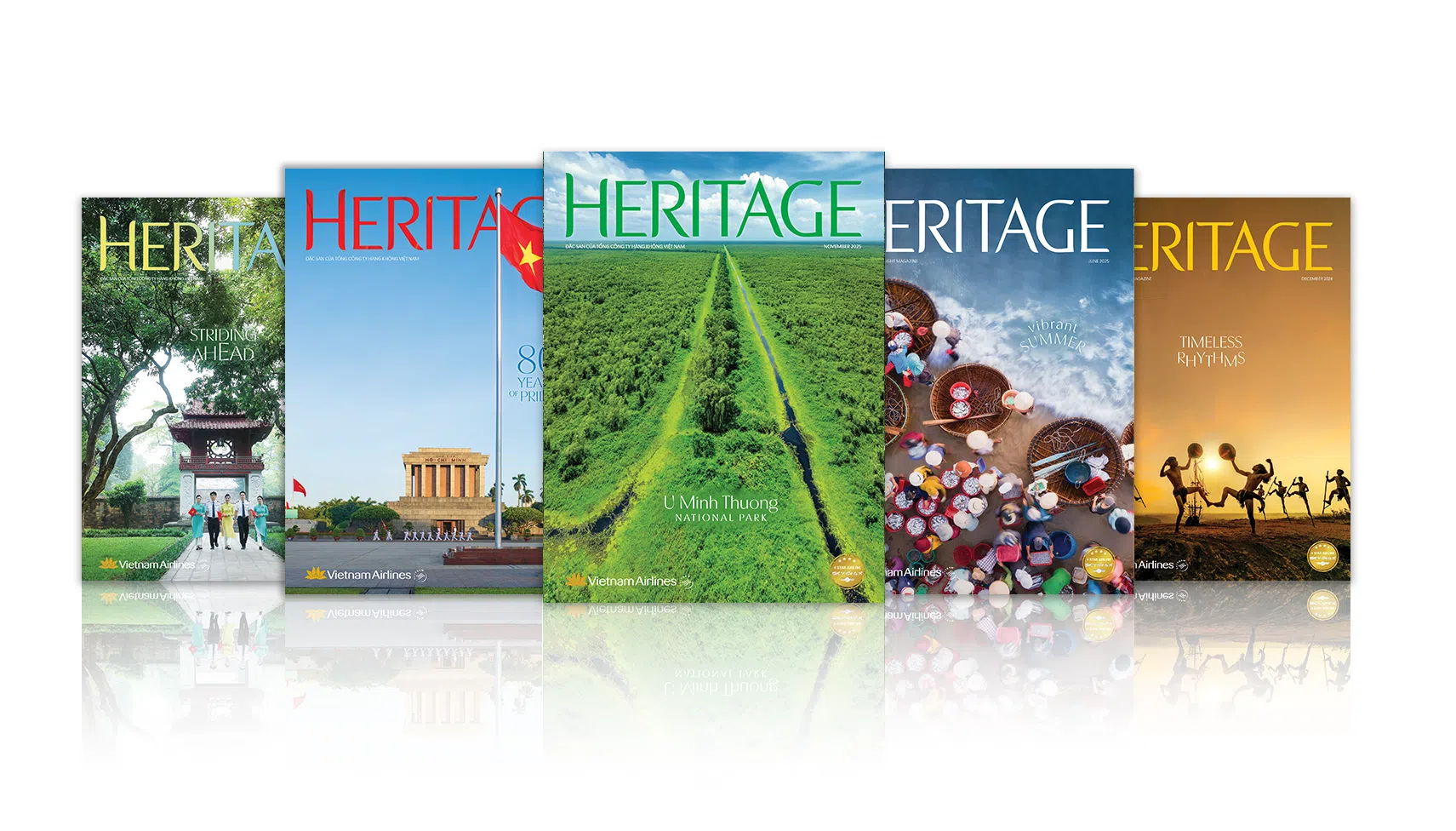

In modern Vietnamese art, the horse continues to inspire. Painter Nguyen Tu Nghiem infused folk spirit into his Giong series, shaping the hero’s horse with rhythmic, elastic lines. Le Tri Dung, who devoted his life to equine imagery, created works such as Red Dream and The Hunt, expressing not only movement but also resilience and inner resolve. Working in ink, painter Tran Huy Duc is celebrated for Hoofprints in the Clouds, where a horse appears to leap through mist, echoing a deep yearning to transcend hardship. Here, the horse becomes a vessel for release from grief. In the hands of today’s artists, the horse is no longer confined by old conventions. It becomes a call to boundless creativity, a figure that bridges tradition and global dialogue, allowing cultural identity and contemporary expression to travel side by side.

From the iron steed of Saint Giong to sacred mounts that bridge the human and the divine, from folk prints to contemporary canvases, the horse has accompanied the Vietnamese spirit across centuries. With each Lunar New Year, when fireworks bloom and imagined hoofbeats echo in the mind, the horse returns as a reminder of vitality and aspiration. It carries the breath of wind, the promise of movement, and the energy of spring.

In Vietnamese culture, the horse is more than an animal; it is a living symbol, a vital spirit shaped by earth and sky. In the rhythm of modern life, as human habits drift farther from nature, the image of the horse – strong yet gentle, loyal yet free – reminds us that true strength lies in harmony, and that the greatest freedom is to live fully in accordance with one’s own nature. The horse represents a longing for freedom, embodied in strength.