Story: Y MY

Photos: INTERNET

Asian cinema often suggests rather than describes, finding beauty in moments of both profound tranquility and fierce intensity.

“Upon the high mountain

One sees everyone

In the lonely village”

Much like haiku poets, master directors of Asia often capture beauty through hints, indirect references and immense empty spaces. They do not attempt to manufacture beauty but allow the beauty of all things to naturally shine forth. Similar to the flowing and recurring four seasons, beauty in Eastern philosophy lies in the absence of worldly concerns and judgments, in simply observing the harmony of things in silence.

Legendary Chinese director Zhang Yimou is renowned for his ability to infuse the spirit of his homeland into every cinematic frame. Audiences are treated to the awe-inspiring majesty of nature with distinctive wide-angle shots that frame humanity as a tiny subject amidst the grandeur. This aesthetic is emblematic of Taoism, cultivating a beauty that is ethereal and brimming with mystique. Most of his films leave a vivid visual impression, accompanied by dominant color themes: the oppressive red engulfing Raise the Red Lantern (1991), the striking hues of House of Flying Daggers (2004) or the dreamy ink-wash painting-like black and white of Shadow (2018).

The beauty in Japanese cinema, meanwhile, is closely associated with two philosophical concepts: “wabi-sabi” (beauty in imperfection) and “yugen” (a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of the universe). Director Yasujiro Ozu stands out with his innovative filmmaking style, which defied Hollywood conventions. Instead of the usual scenes transitions, Ozu inserted still frames, such as buildings, a teapot, a tree branch, or a vast expanse of sky, to moderate the film’s drama. This tranquility might cause the films of Ozu or fellow Japanese director Akira Kurosawa to be considered difficult to watch. But a careful viewing elicits curiosity behind the relaxed pacing, as the directors pick beauty from small details and stir their audiences through calm observation.

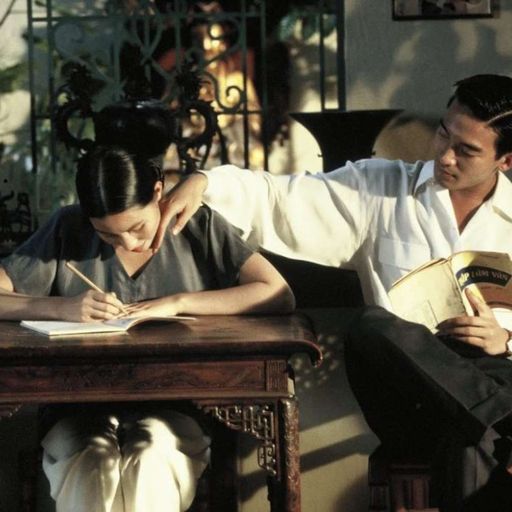

Among renowned Asian filmmakers operating in the West, Tran Anh Hung shines as a distinctive Vietnamese face. The aesthetic sensibilities in each of his films have captivated a global audience with a breathtakingly beautiful Vietnam. From the scenes of Hanoi in Vertical Rays of the Sun (2000) to the Northern Vietnamese family space in Saigon of the 1950s in The Scent of Green Papaya (1993), Tran Anh Hung’s films express an intense human psyche through a slow, gentle and soothing rhythm. Audiences often observe the director’s close-ups of eyes, sunlight and objects as a series of metaphors for the messages the characters wish to convey. Tran Anh Hung’s skillful integration of Vietnamese music also creates an emotionally rich and nostalgic local atmosphere, contributing to his prestige worldwide.

An extreme asian cinema

Alongside subtlety and an emphasis on imagery, Asian cinema also exhibits vibrancy and intensity, especially in the shocking and edgy work emerging from South Korea.

If the scene of a serene lake surrounded by rolling mountains can make one forget their worldly concerns, then within that silence and peace, director Kim Ki-duk can still stir up the most extreme ideas. The dramatic rhythm set against the backdrop of Buddhist philosophy in Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003) illustrates the intersection of Korean-style quietness and intensity.

The film pushes all contradictions to their maximum, sparing the audience the need to distinguish between fear and pleasure or right and wrong, discarding all moral standards.

The beauty of South Korean cinema is born out of the spiritual torment and extreme hardship of a nation that has lived through many upheavals. Where does Korea stand in the global tide of capitalism? How have the South Korean people lived in the face of social changes and stark polarization as we see today? When a country goes through rapid modernization, the inevitable consequence is self-denial and societal instability.

From this background, moral values are challenged. Class conflicts deepen and are magnified in cinema, much like the violence of driver Ki-taek (actor Song Kang-Ho) against his wealthy employer Mr. Park in Parasite (2019), because he showed a slight disgust towards the smell of the poor. Parasite went on to make Oscars history as the first foreign-language winner of Best Picture.

Whether serene or extreme, Asian cinema maintains an inherent allure. In all its diverse variations, the aesthetic of Asian film is indelibly anchored in the philosophies of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Even with the ongoing process of globalization, the distinguishing characteristics that set Eastern and Western cinema apart remain undimmed. The Asian essence continues to be perpetuated through the language of film.