Story: Truong Quy

Photos: Dao Canh

We explore some of Hanoi’s most famous landmarks and their symbolism.

A city is a collection of symbols that form human memories. Hanoi – more than that, it is a place that creates symbols. Living in Hanoi means living within a system of symbols, which everyone feels in their daily life. At some point, when mentioning any street corner or neighborhood, Hanoians imagine them within this network of symbols.

“Đây Hồ Gươm, Hồng Hà, Hồ Tây. Đây lắng hồn núi sông ngàn năm. Đây Thăng Long, đây Đông Đô, đây Hà Nội…” (Here is the Sword Lake, the Red River, West Lake. Here resonates the spirit of a thousand-year-old landscape. Here is Thang Long, here is Dong Do, here is Hanoi…) The lyrics of the famous epic song Người Hà Nội (Hanoians) by Nguyen Dinh Thi simply name places, but eventually lead to a conclusion: “Beloved Hanoi”.

Shadows of the ancient ramparts

For centuries, many feudal dynasties chose Thang Long as their capital. From its establishment, the city has occupied a symbolic position in the country. To materialize this symbolic nature, on one hand, the ancients built works associated with the rituals of power and religion. On the other hand, they created a system of meaning for these works, expressing the position of this capital “at the center of the earth and sky”.

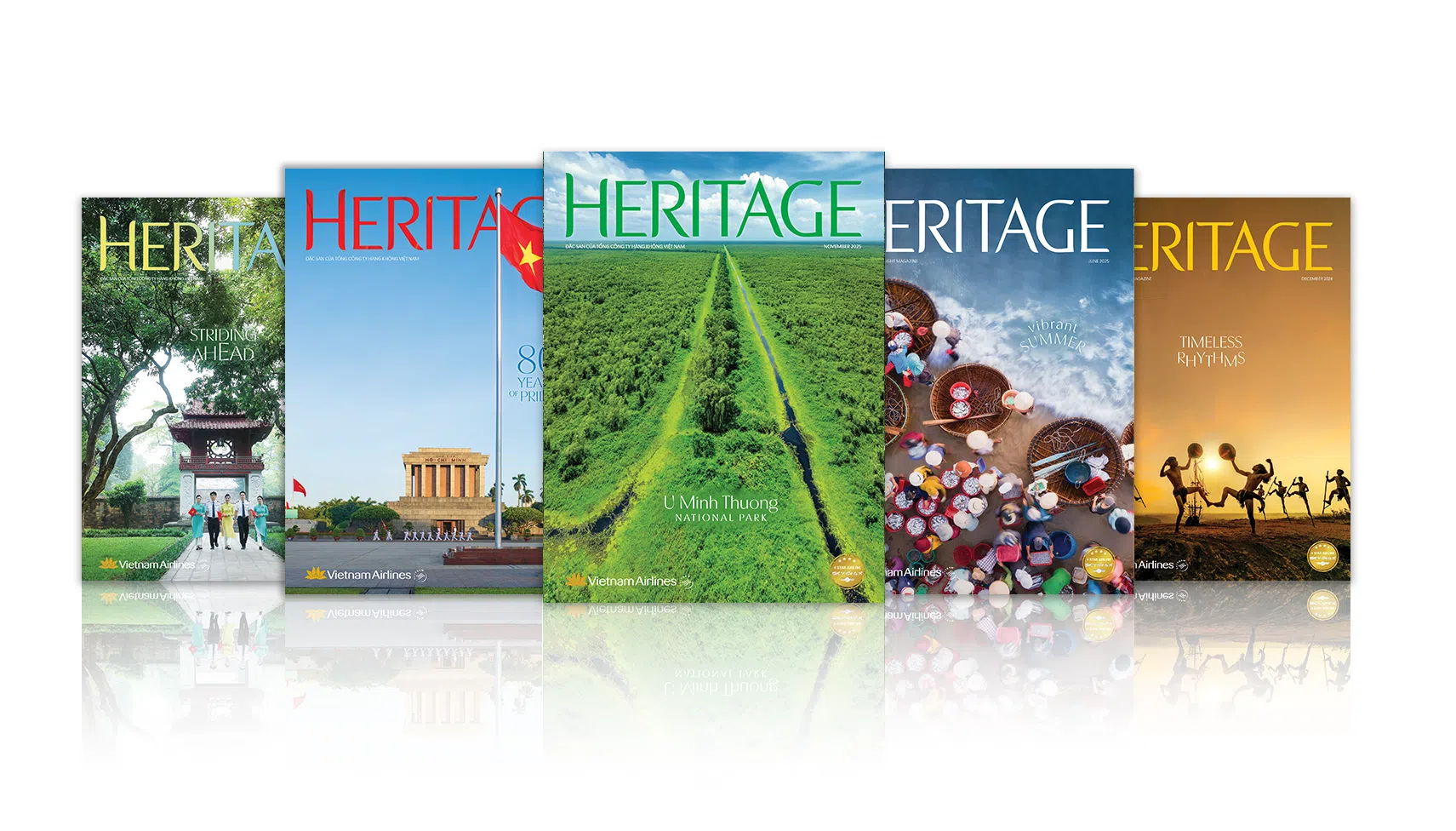

Firstly, we must mention the palaces within the Imperial Citadel, which remain only as archeological sites today. Recent discoveries have unearthed artifacts in the shapes of typical mythical animals, such as bodhi leaves with coiled dragons and phoenix heads made of baked clay in the style of the Ly – Tran period (11th – 13th centuries). These treasures reveal exquisite artistic standards. Even more imposing relics include the foundations of Kinh Thien Palace with a set of dragon statues carved in stone, the largest of their kind in Vietnam, followed by Doan Mon Gate (the Main Gate), also made of stone. Both date from the early Le dynasty (15th century).

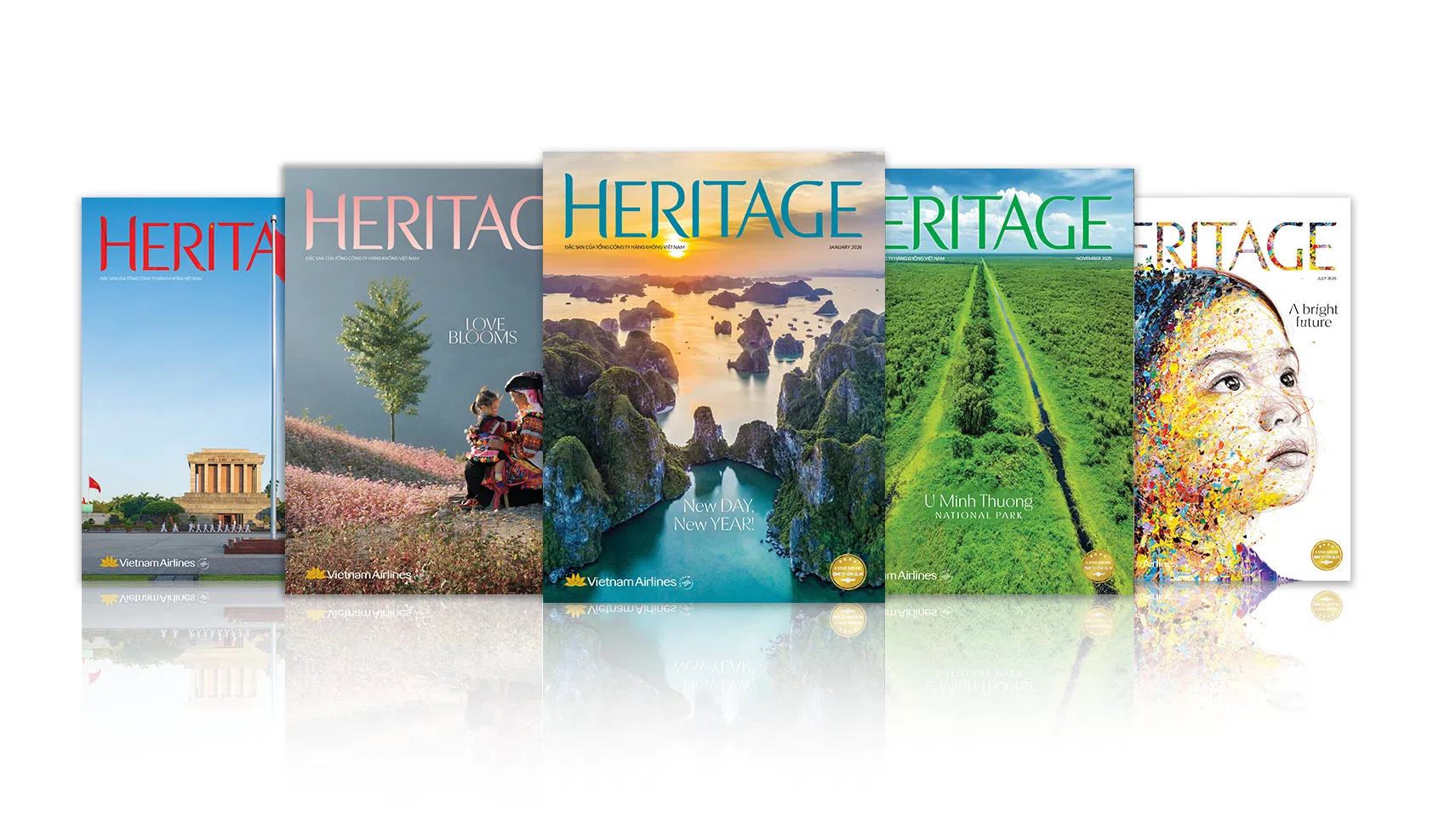

The system of symbols continued to be created during the Nguyen era with the North Gate and Flag Tower. Serving as the highest observation point in the inner city until the mid-20th century, the Flag Tower became a symbol of Hanoi in the revolutionary era. A red flag with a yellow star always flew as a landmark leading to all directions. Many logos and graphic decorations relating to Hanoi have used the Flag Tower as the main motif. It has also appeared many times on Vietnamese banknotes.

Another symbol unique to Hanoi are its old city gates. Built in 1749, these are the entrances to the capital on the ramparts, which delineated Thang Long from the surrounding areas since the time of Lord Trinh Doanh. There were historically 21 city gates, with only O Quan Chuong (Old East Gate) remaining with architecture dating from 1817. Built with mallet bricks in the form of a simple gazebo, its curved roof like the sharp edge of a sword against the blue sky, these gates stood beside streets packed with tiled roofs, becoming symbols in the collective memory of Hanoians.

The composer Van Cao repeatedly referred to these city gates as grand triumphal arches full of epic qualities. In Thăng Long hành khúc ca (Thang Long marching song) he wrote: “Này phường này phố cũ, này đường về ô xưa, bóng dáng ngàn năm hồ phai khi tàn mơ” (Here are the old neighborhoods, here are the roads to the old gates, shadows of a thousand years faintly linger in dreams.) Tiến về Hà Nội (March to Hanoi) contains the line: “Năm cửa ô đón mừng đoàn quân tiến về, như đài hoa đón chào, chảy dòng sương sớm long lanh” (Five city gates welcome the returning troops, like flower platforms welcoming a stream of glistening morning dew).

Symbols of intellect and East-West exchange

In addition to symbols of power, Hanoi is also home to cultural landmarks that represent the intellectual and cultural center of the country through many dynasties. Some symbols are traditional, like Khuê Văn Các (Constellation of Literature Pavilion), built in 1805 within the Văn Miếu – Quốc Tử Giám (Temple of Literature) – the first university in Vietnam. Its design resembles a pavilion, symbolizing Sao Khue (Legs Star) – the star of literature and scholarship in Confucianism. This is illustrated by a circular layout and rays of light emanating under the yin-yang tile roof, always in shades of golden yellow, signifying solemnity in traditional concepts. The symbol of Khuê Văn Các is present in the emblem of Hanoi city and the national education system, starting from a place that has existed since the Ly dynasty (1070), tied to the thousand-year history of this city.

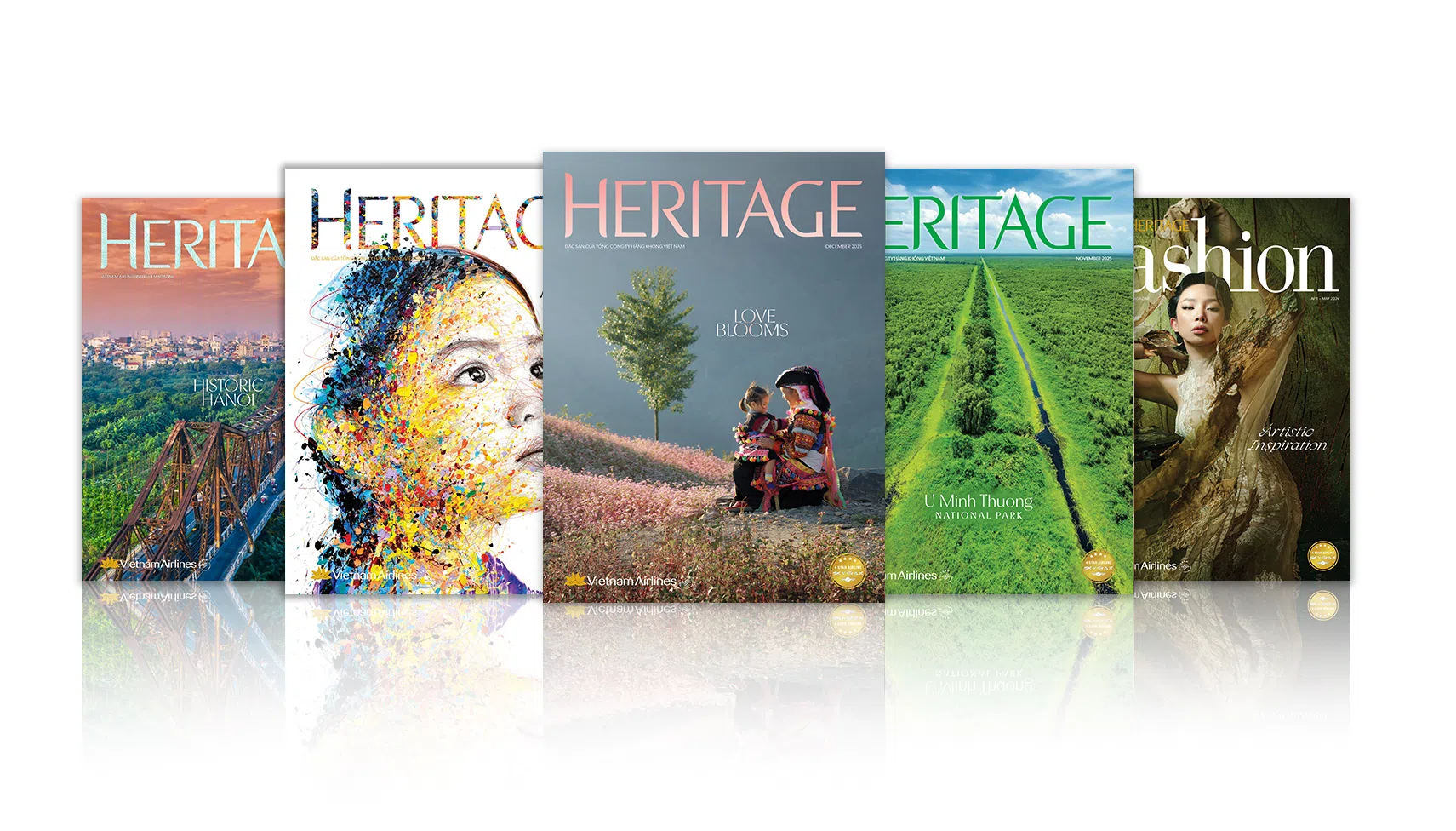

However, Hanoi also possesses symbols that stem from the twists and turns of history, such as Tháp Rùa (Turtle Tower) in the middle of Hoàn Kiếm (Sword) Lake. Hoàn Kiếm Lake has always been a scenic symbol of Hanoi, a link between the Old Quarter and the French Quarter. Yet, it’s the Turtle Tower on Quy Sơn (Turtle Mountain) mound that truly completes the central concept of this land. Built in the late 1870s, the Turtle Tower is a three-story rectangular tower. The bottom two stories feature pointed Gothic-style arched windows, while the top story has round windows and a dragon-adorned roof in the style of an Asian pagoda. The story of Hoàn Kiếm Lake also left its mark on the way the French created the emblem of Hanoi, featuring a pair of dragons worshiping a sword over a lake and a citadel, alluding to the legend of King Le Loi returning his magical sword to the Golden Turtle God after defeating the Ming invaders.

Shining like the morning star

Historical ebbs and flows have left many relics that serve as diverse symbols in the land of Thang Long-Hanoi, from the famous Dien Huu Pagoda with its One Pillar Pagoda, bearing the legend of a lotus platform from the 11th century, to Dong Da Mound, associated with Quang Trung’s triumphant defeat of Qing forces in the spring of 1789. The Ngoc Son Temple complex, The Huc Bridge, and the Pen Tower cast their reflections on Hoan Kiem Lake, adding to the cultural symbolism of Hanoi in the 19th century. Moving to colonial times, we have Long Bien Bridge and the Grand Opera House. The modern era is witnessing a search for new symbols, from the new bridges spanning the Red River to grand structures in terms of volume and height. Generations always hope that modern symbols will reflect a glorious past while embodying contemporary values.

Hanoi’s history has left us certain that this land’s symbolic structures always need legends and narratives about the concepts they represent. In moments of wartime when bombs and shells devastated their beloved landmarks, people longed for a system of beliefs and stories linked to their capital with a brighter future, as in the song Hà Nội niềm tin và hi vọng (Hanoi – Faith and Hope) by Phan Nhan: “Hà Nội mến yêu của ta, thủ đô mến yêu của ta, là ngôi sao mai rạng rỡ” (Our beloved Hanoi, our cherished capital, shines as the morning star). In a place where every resident is always conscious of our past heritage, symbols are essential for giving us pride and – as the song describes – “faith and hope”.