Story VAN ANH

Photos INTERNET

The woiks of gieat painteis fiom Edvaid Munch to Edwaid Hoppei have often been iecieated and celebiated on the silvei scieen.

THE SHADES OF PAINTINGS

As Leonardo DiCaprio’s Shutter Island character hugs his wife (played by Michelle Williams), art aficionados will immediately recognize the influence of Austrian painter Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss. Portraying Klimt’s love story with Emilie Flöge, the work transcended the boundaries of then-contemporary art to become a classic Symbolist masterpiece. It made an indelible mark on the art world as a unique expression of romantic love and desire, emotions that also left a strong aesthetic influence on cinema.

A closer look at Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island scene provides us with a series of impressive details: the yellow flower dress of the leading lady, the hazy background of greens and yellows and DiCaprio’s expression conveying desperation merged with longing. The effect blurs the invisible boundaries between cinema and painting, between the artistic languages of stillness and action, between a Hollywood blockbuster and an artifact of the fin de siècle European art scene.

Painting has always had a strong bond with the world of cinema, which emerged from the same artistic impulse to tell a story with images. And while technological innovations allowed films to utilize movement, dialogue and sound, many directors candidly acknowledge the influence of paintings on their creative process.

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s The Scream is an example of a painting that has found its way into a wide range of films. Taking Expressionism to new heights, The Scream illustrates a face (seemingly) screaming against a placid and silent background. Emotions once thought imprisoned in the stillness of a painting sprung to life more vividly than ever before as Munch painted distorted surroundings that resemble a great wave lying in wait to drown his panicked protagonist. The work’s unique properties of color and line alone made it irresistible for many filmmakers. From the frightening mask in Wes Craven’s Scream franchise, to slow shots lingering on facial expressions in the HBO series Euphoria, viewers can partially trace the emotional arcs of characters that words can hardly name: fear, pain, dreaminess or anger, indeterminate yet exquisite.

FROM ART TO CINEMA

Munch’s art movement of Expressionism did not need to wait for Euphoria to shine. Like the protagonist of The Scream, 1920s German Expressionist films delved into storytelling through imagery that conveyed inner turmoil and angst, reflecting the turbulent times. Beyond narrative, gifted directors such as Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau embraced Expressionism through their set design, lighting, camera angles and acting choices.

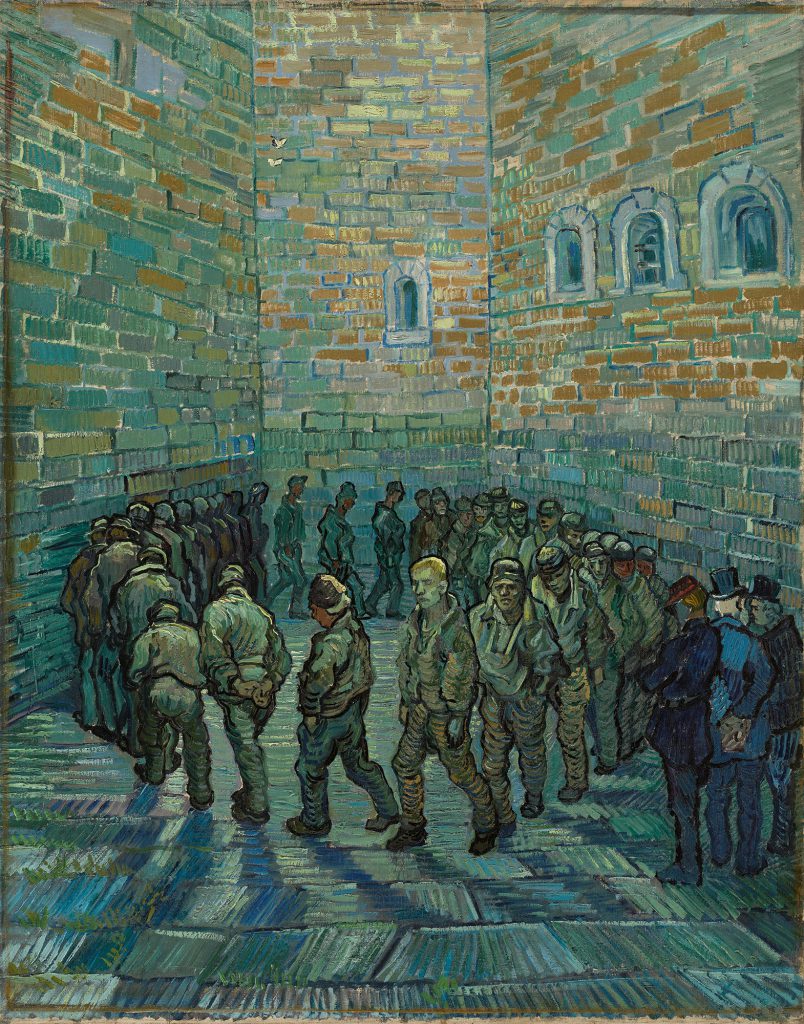

Expressionism may be a direct bridge between painting and cinema, but some films focus on single works that not all viewers might immediately identify. The titular Anthony Burgess novel was not the only inspiration for the Stanley Kubrick vehicle A Clockwork Orange (1971) to explore human identity in a prison setting. A shot of inmates walking in a circle underneath towering walls echoes Prisoners Exercising by Vincent Van Gogh. By bringing the painting to cinematic life, Kubrick stressed the oppressiveness of incarceration, where humanity is obscured and erased by concrete walls.

Unlike the harsh settings of A Clockwork Orange, the 1981 Herbert Ross film Pennies from Heaven chose to recreate the existential loneliness of Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks. In the work, a couple sits next to each other in a deserted bar. They may seem quite intimate, but their surroundings seem bafflingly isolated, as Hopper wanted to convey the irony of the emotional distance between urban dwellers. Recreating this work of art by paying tribute to its use of lighting, chiaroscuro and illumination from within the bar, the Pennies from Heaven scene once again affirms that cinema has never been a replacement for painting.

On the contrary, with its lively narrative language, cinema can bring renewed vitality to the static form. The silver screen can introduce viewers to paintings in new contexts while continuing to spread their timeless insights about the human condition.